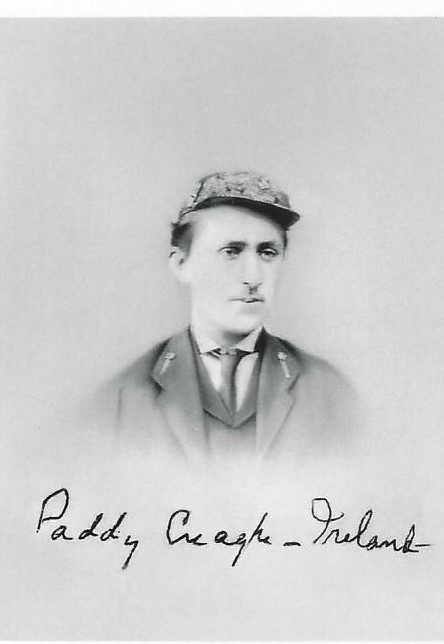

20 Jan Gerald Francis Creaghe

1856-1880

Ca. 1870

Photo cortesy of Mary Creaghe ( Corning) Penfield

On February 22, 1856, Gerald was born the seventh child of nine and sixth of seven sons to Richard F.H. Creaghe and Anna Maria Archer-Butler in Ireland. Little is known of his childhood. The earliest written evidence was found by Michael Barnett when he noted “a strange note at the back of the manuscript book of the Letters of Harry Alington Creaghe” as noted below:

In a dream my darling Gerald had a few nights before he was taken dangerously ill the Christmas of 1866 – “I dreamed that I was dying and that I had all my dear brothers and sisters around my bed. I suddenly fell into a deep sleep and when I awoke out of it I looked about but could see no one, everyone had left now, and I was alone. But I did not remain long before I was startled by the rustling of wings and soon saw a beautiful angel all dressed in white who laid a white tablecloth on my pillow and flew again up to heaven. I looked at the tablecloth and there was written in letters of gold “three words” – “Are you ready?”

Gerald Francis Creaghe, December 20th, 1866

I believe the first sentence of the passage can be read as an introduction by Harry to a dream related by his “darling Gerald” and mailed to Australia soon after December 20, 1866. In letters home in April and July, Harry does not mention his brother, but in a letter to his mother dated August 5, 1867, expresses concern for his younger brother by seven years, who was then eleven years old, “… delighted I was to see by yours that you are well again at home except poor darling Gerald, whom I thank God almighty is quite well again.” We cannot know if the dream was related to the illness mentioned above, but if it was, then the boy must have been quite ill for some time. Regardless of when he was sick, it must have been a serious problem. We can conclude that the young Gerald was a spiritual lad and, perhaps, prescient. Although Gerald was quite ill around that time, it is apparent he was not “ready”.

It can also be inferred that the prospects for young men in Ireland in this family in the 1860’s and 70’s were not promising in that five, including the eldest (Richard, Harry, St. George, John, and Gerald) of the six surviving boys left Ireland to seek their way in the world. (Gerald, age eighteen, immigrated to America with his big brother, St. George, who was twenty-two at the time. Remarkable things were expected from young men in those times.

After departing Queenstown (now Cobh, County Cork), Ireland aboard the SS Egypt, the lads arrived at the port of New York on July 20,1874. Shortly thereafter they moved on to New Orleans, most probably by ship. There they could well have found lodging in the neighborhood known then, as now, as the “Irish Canal”. As related by George Creaghe (1924-2018), grand-nephew of Gerald, the first job for the young immigrants was common labor – digging canals in New Orleans. This was brutal work in a brutal climate. These laborers were considered expendable. In fact, in antebellum times, slave owners would not rent out their slaves for the work because the mortality was too great. So, let the Irish do it.

It did not take long for them to figure out that there had to be a better way to make a living. Soon they were off to the gold and silver mines of Colorado in Gilpin and Clear Creek counties just west of Denver. There they did more labor work in the mines, but also tried some cowboying and got exposure to the ranching business. They saved what must have been a significant amount of money, gathered information, and made a decision to move on.

That move was to northeastern Arizona Territory in 1874. Somehow, they had enough capital to buy a ranch in the Coyote Creek area about thirteen miles east of Round Valley, now Springerville. The nineteen and twenty-two year old men were among the first settlers in this brand new town.

Somewhere along the line, Gerald picked up the name “Paddy”. This was initially concerning in that it was a disparaging name that applied to male Irish immigrants to the U.S. in the mid to late 19th Century (Bridget, Biddie, or Bidde for females). However, Caroline Blunden gave assurances that “Paddy” should not necessarily be taken as disparagement in that it is acceptable for one Irishman to use the name for a friend even if their given name is not Patrick. Also, Gerald and his big brother do not seem to have been the kind of men who would have put up with a nickname if it were offensive.

According to George Crosby’s article in the St. John’s Observer, August 8, 1924, in addition to ranching, both men were also interested in politics – Gerald more so than St. George. “Had he lived, he would have been a big man” in the area. Gerald’s public service career began as early as 1877 when Sheriff Edward Bowers of Yavapai County appointed him Special Deputy. Later, in late 1878, he was elected Constable of Springerville.

The huge Yavapai County was split on February 24, 1879; the eastern half became Apache County. On June 2, Luther Martin became the first elected Sheriff of the new 21,177 square mile county. He then appointed the twenty- three-year-old Gerald as Undersheriff. The role of Undersheriff (or, in New Mexico, Chief Deputy) was quite significant and not lightly bestowed. The responsibilities included taking over for the High Sheriff if he was unable to perform his duties. Soon thereafter, Gerald prevented the lynching of a murderer, Jack Burke, in St. Johns. He was on his way in the world of the Arizona Territory law enforcement and politics.

A Capt. Creaghe, presumably Gerald, was tasked with the responsibility for “Guns and Conveniences” for the 1879 July 4 celebration in Iron Springs near Prescott-over 200 miles from Springerville. It is not clear what the “Capt.” designation implies. Note that Iron Springs was not a part of Apache County at that time. Perhaps it was something left over from his Deputy Sheriff days in Yavapai County. He seems to have been developing a presence beyond his hometown.

There is nothing else that has come to light thus far that sheds light on his personal life, love interest, letters home; he seems to have been well liked and respected by his peers in the Arizona Territory. Interestingly, it appears that he never became an American citizen.

As early as early as 1876, Gerald became acquainted with another man, James Richmond, and their fates became entwined.

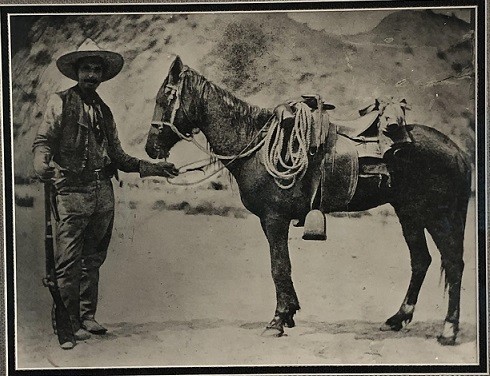

James Almeron Richmond

1844 – 1880

Dorotha Simmons Piechocki

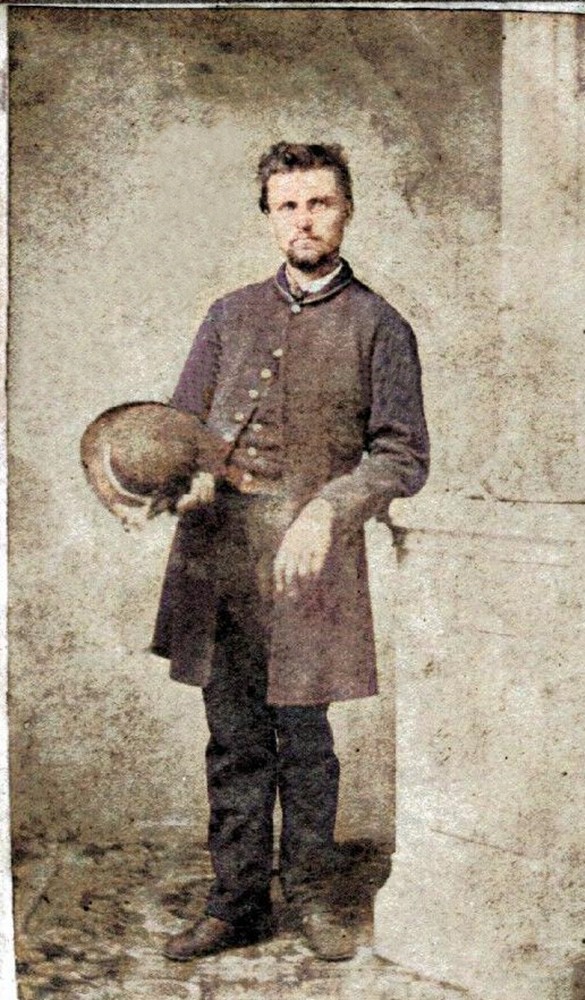

James Almeron Richmond was born 21 Aug 1844 in Ohio City (later annexed by Cleveland), Cuyahoga Co., OH, the 2nd child and first son of Martin Sylvanus and Mahalath Bedford Richmond. Enlisting at age 18 in the 103rd Ohio, James served with the Army of the Tennessee from 1862 through 1865, participating in such battles and campaigns as Monticello, Jonesboro, the siege of Knoxville, Kenesaw Mountain, Decatur, the siege of Atlanta, Franklin, Nashville, the capture of Wilmington, and the surrender of Johnston.

James’s family had moved in 1863 from industrial Cleveland where his father Martin had worked as a blacksmith for 30 years to rural Keene Twp., Ionia Co., MI, where he became a farmer. It is very likely that when James arrived back in Cleveland in June 1865, there was no welcoming family for him. We know from later family reports that after the war, James rejoined his family in Michigan and although he had no physical wounds, it appears that he was unable to “settle down.” After a short while in Michigan, he left with his younger brother Albert, also a Civil War veteran, for the adventure of the West. By 1870, Albert had met a girl in Iowa and taken a job as a farm hand, marrying the following year and soon becoming a father. When Albert’s wife became ill, he returned to Michigan with his young son, and James accompanied them, visiting his aged parents for the last time. But he did not stay.

In April 1876, James was enumerated as a resident of Springerville, Yavapai Co., Arizona Territory on a Voter Registration. In the same year his name appeared on the Territorial Census record for Clear Creek, Yavapai Co., Arizona. James Richmond also had an account at the Becker Bros. Store in Springerville, where his name was in the ledger books for purchases on credit in March 1876. (He liked to buy oysters!) On 17 Oct 1878, James’s name was again listed on the Voter Registration for Pima County, which had been split off from Yavapai Co. By 1880, Springerville had a population of 364. James would have been well-acquainted with the Creaghe brothers, fellow ranchers. By Spring of that year, both James and Gerald had been appointed deputies by Sheriff Martin, Apache County. About that same time significant unrest in the native population of Apacheria – eastern Arizona and western New Mexico Territories -came to a boil in their area.

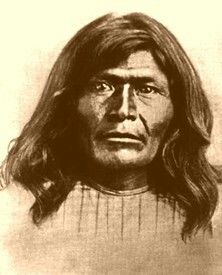

Victorio

1820s – 1880

The third player in this drama was the Apache Chief, Victorio, also sometimes known as Vittorio. Born sometime in the 1820’s, Victorio was a contemporary of famous war chiefs of the Apache Nation in the second half of the 19th Century, such as Cochise, Nana, and Geronimo. He was a leader of the Chihenne, one of the four bands of the Chiricahua Apache tribe, who was either a freedom fighter, renegade, insurgent, or terrorist, depending on one’s point of view. Actually, he was all of these things, as well as an effective, experienced, charismatic leader who inspired fanatical loyalty in his followers. He used his intimate knowledge of the environment in hit and run guerrilla tactics, moving quickly over formidable terrain and using international borders to discourage pursuit. This should sound familiar to an early 21st Century reader.

The Chihenne homeland for many years, Warm Springs, was in a forested region between the Black Range of the Mimbres and San Mateo in southwestern New Mexico Territory. Think southwest of present-day Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. In the 1850’s and 1860’s, enlightened Indian agents lobbied for the area to be designated a reservation for the Chihenne people. However, for the usual reasons, they were moved west in 1872 to the Tularosa Reservation and finally, in 1877, even further west to the San Carlos Reservation in south-eastern Arizona Territory. The reservation actually protruded in to the southern most part of what was then Apache County. The Chihenne hated it there. The land was inhospitable, and they were forced to live with other tribes that had been and were still enemies. Victorio and a band of followers became fugitives in the Warm Springs area rather than submit. Finally, in September 1879, he had had enough and started what became an ongoing armed conflict – Victorio’s War.

The band initiated hostilities with a horse stealing raid on the 9th Cavalry Regiment on September 4. Over the next two months, he fought engagements with the U.S. Cavalry and raided remote ranches and mines, killing civilians and terrorizing the population as he went. The continuous fighting, raiding, running, and hiding in the New Mexico mountains took its toll. Victorio moved into Mexico to regroup, rest, and raid. However, there the Indians were pursued by the Mexican Army. In early January 1880, Victorio brought his followers back into New Mexico.

They resumed their previous pattern of raiding and terror in western New Mexico. The 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments (the Buffalo Soldiers) opposed and pursued the Apaches relentlessly. Any intrusion into Arizona was met by elements of the 6th Cavalry. All of the cavalry regiments were supported by Indian scouts, most Apache. The process was exhausting for both sides. When pressed, Victorio’s band would scatter into the Black Range and Mongollon Mountains just to the east of the Arizona-New Mexico line.

Part of what was influencing Victorio’s decision making was that he and his group had family members who were still being held in the San Carlos Reservation. Also, at the reservation, were sympathetic Apache warriors who were eager to join his forces.

After about four months of this pattern of raiding, pursuit, and hiding, Victorio attacked a silver mine near Alma, New Mexico on April 28,1880, killing six. Following this attack the band ranged around the area, killing about thirty-five more people – mainly sheepherders and their families – and slaughtering thousands of sheep. This continued until troops arrived from Ft. Bayard near Silver City sixty miles to the south.

The report of the commanding officer, Captain Malden, dated May 8, stated that he left Silver City with his troops on May 4 and arrived at “the head of the San Francisco River” on the evening of the 8th. The San Francisco River flows just south of Alma; just what he means by “the head of the river” is not clear. By that time, his force had been traveling “hard for three days and two nights in pursuit of Victorio’s Indians, but they are still a day ahead of me… they have so far, to my knowledge, killed eleven men, two women, and four children and I have heard of 20 others being killed.”

Out of food and horses spent, Malden reported that he had to give up the chase. He wrote, “Everything now leads to the belief that they were heading for Stevens Ranch or somewhere in that vicinity to procure ammunition… The country people in this region are fearfully excited and whole settlements are being broken up.” The Stevens Ranch was located “on Eagle Creek …, not far from the mouth of Willow Creek.” (Farish)

It seems likely that at this point Victorio split his forces. He again took the bulk of the band into the mountains to the east to elude pursuit. A smaller group of approximately forty warriors were sent to the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona and to the Stevens Ranch. Robert Utley thinks that this band was led by Washington, Victorio’s “aggressive daredevil” son with the goal of freeing their families and picking up some new recruits at San Carlos. Others feel the group could have been led by Victorio himself. Whoever it was, Victorio was commonly given credit for things he was not personally involved in, thereby adding to his mystique.

The San Francisco River leads directly to Clifton, Arizona about forty miles downstream to the southwest; Eagle Creek and the Steven’s Ranch site are another twenty-five miles to the west.

Somewhere around May 1, Apache County Sheriff, Luther Martin, dispatched Undersheriff Gerald Creaghe and Deputy James Richmond to assess or collect taxes in the far southern part of the county. Tax collection and assessment were part of the duties of the Sheriff’s office. Communications were not as timely in those days; telegraph was the quickest but not totally reliable. Victorio had been on the warpath for eight months by that time. Most of the activity was just east of Apache County in western New Mexico. There was unrest in all Apache reservations, but particularly in the San Carlos Reservation in southern Apache County.

The two deputies were certainly experienced, but surely the decision to send these two men alone into this area of unrest was not taken lightly. None the less, it turned out to be fateful. It is reasonable to assume that the “highway” they took from Springerville to Clifton was the Coronado Trail, now Arizona State Highway 191. The further south Gerald and James traveled, the closer they got to where the war was actively taking place. It is 120 miles to Clifton and at some points is no more than six miles from San Carlos. After calling at Clifton, the two men headed north, perhaps planning to call at Stevens Ranch. One can assume ranchers paid taxes also. They stopped and “camped for dinner” on Eagle Creek near where Willow and Ash Creeks empty into it. This was probably just south of Stevens Ranch or perhaps even on the ranch itself.

George Stevens had a fairly large operation with both cattle and sheep herds. The story has it that his wife was a daughter of Cochise or even Victorio, and there were always groups of friendly Apaches hanging around. The raiding band of Victorio’s warriors first struck the ranch, killing some sheepherders and White Mountain Apaches, and then made off with horses and cattle. Word of the attack and a plea for help was sent to Camp Thomas thirty-five miles to the west. Legend has it that an Indian woman carried this message on horseback.

Captain Ned Kramer of the 6th Calvary Regiment received word of the attack at about noon May 7. He immediately left at a rapid pace with twenty troopers and an equal number of Indian scouts. A pack train with more supplies followed sometime later that afternoon or evening.

Probably in the late afternoon or evening hours Kramer’s force was ambushed on Ash Creek near the Stevens Ranch. After a sharp fight, the hostilities broke off, and the Indians rapidly retreated. He estimated their strength at “between 40 and 50 bucks and 36 animals”. Veteran Sergeant Dan Griffin was killed, and a scout wounded in the clash. The cavalry pursued the fleeing hostiles, and, after a nine-mile chase, the Indians stopped to fight again. A flanking maneuver by the scouts caused the Apaches to again break off and retreat rapidly eastwards toward the mountains. Kramer pursued, but was unable to catch up. He then pulled back about four miles and went into camp for the night.

The next morning, May 8, the pack train and reinforcements arrived. Also that morning the troopers discovered other evidence of war: “The bodies of two unknown white men, supposed [today, the word assumed or presumed would be used instead (DSP)] to be prospectors were found near my present camp; also one wounded Mexican sheepherder. All the work of these Indians.”

The preponderance of evidence now available indicates that these two men were Gerald and James. Word was that they were surprised as they camped for a meal near the Ash Creek – Willow Creek – Eagle Creek confluence. George Hiller wrote a letter to James’s family from Camp Thomas published June 2 that states that the two men were killed “at Steven’s Ranche.” The same news was on the telegraph wires by May 11: “P. Craig[sic] …James Redmond[sic] ..at Steven’s Ranche.” This could have well happened after the raid on Stevens Ranch but before Kramer’s arrival on May 7. It can be reasonably assumed that the army buried them where they were found. There would have been no time for a marker of any permanence.

The attackers were vigorously pursued but not contacted by the Cavalry forces. It is possible that Washington and his raiders rejoined his father’s band in the mountains of New Mexico. Victorio’s band was not definitely seen again until May 13th, just before he attacked Fort Tularosa (near Aragon, New Mexico) the next day. After that the group continued raiding in southern New Mexico Territory and into Mexico. On October 15, 1880, they were finally fixed in position by a unit of the Mexican Army in the mountains and hills of Chihuahua.

At dawn, the army attacked. The eventual outcome was obvious to all. As the battle progressed, the Apaches were reduced to a wounded Victorio and a small group of warriors including two of his sons – perhaps one was Washington. Out of ammunition, the group was cut down one by one until only Victorio and three others remained at the top of the hill. ” They stood as demigods of old – alone bloodied, distaining surrender, with nothing left to fight with but their knives As the Mexican soldiers approached, the four Apaches plunged their knives into their own hearts. The last stand at Tres Castillos was over.” (Hutton, p.258) Some women and children survived. Most were sold into slavery or, if children, taken into Mexican households. As with many insurgencies, these people were, in the least, committed.

Still, we are left with many significant questions unanswered. According to family legend related to me in the 1950’s by my grandmother (Nellie B. Creaghe, 1894-1977), the killers cut off Gerald’s finger to steal his signet ring (CFHS – Artifacts – St. George Creaghe’s Signet Ring) given to him by his father before leaving Ireland. Another account states they were scalped. This is possible. The Apaches had co-opted the practice in 1837 when the Mexican government began offering 100 pesos for a male Apache scalp – less for women and children’s. If so, who first told the story? Whoever it was must have known where they were buried. For many years, before it was lost, James’s family held an arrow shaft that was removed from his body; how did the family come by it in the first place? Family legend says “it was returned with his personal effects” to Michigan, but who found and retrieved it and under what circumstances? Based on the date of inscription in Gerald’s hymnal (CFHS – Artifacts), his family must have gotten word within two days – how? Where is the letter George Hiller wrote to the Richmond family from Camp Thomas on June 2, 1880? Perhaps it was full of details. Where did he get his information? How did he know who to write to? Perhaps, someday we will have these answers.

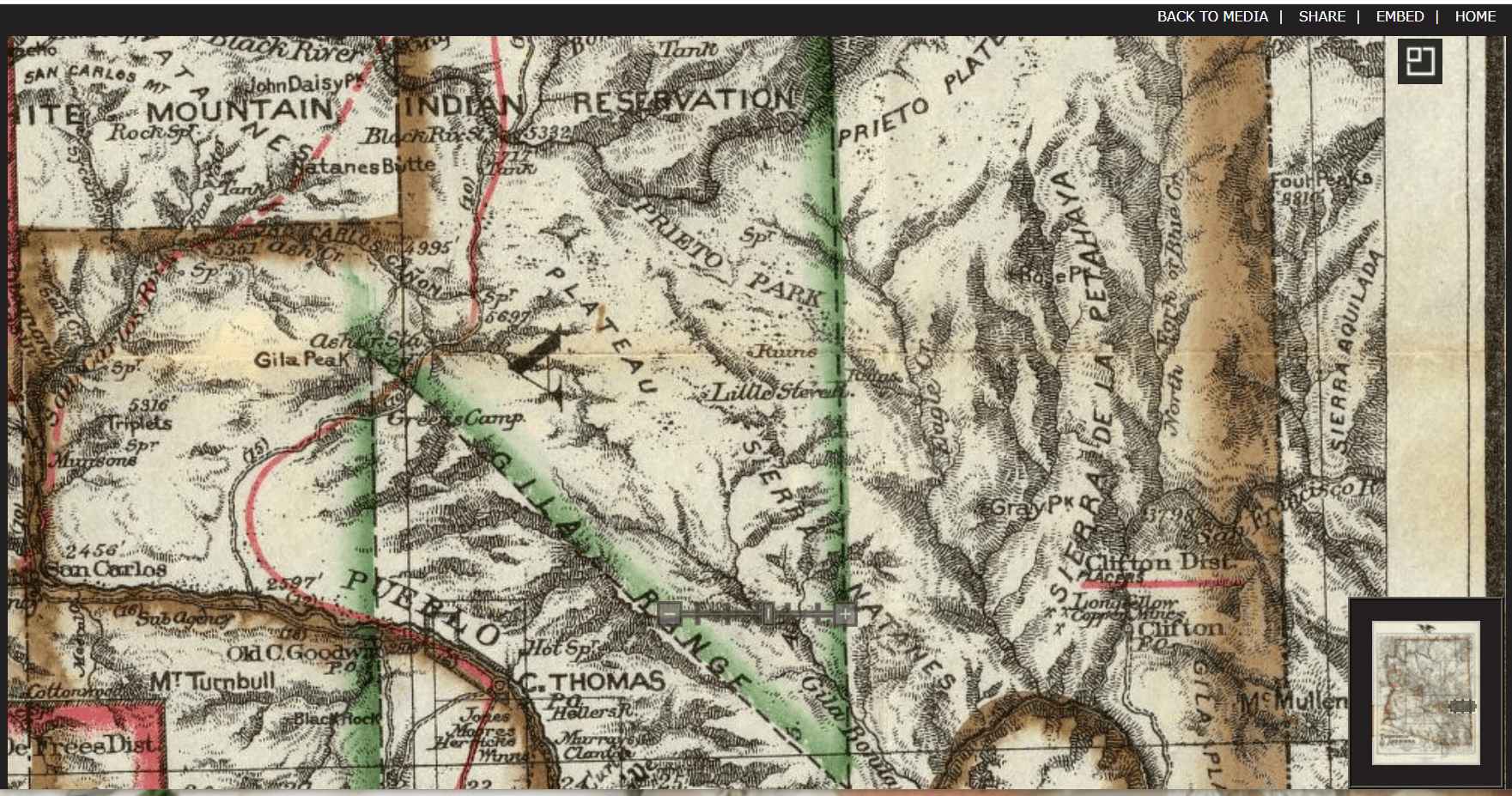

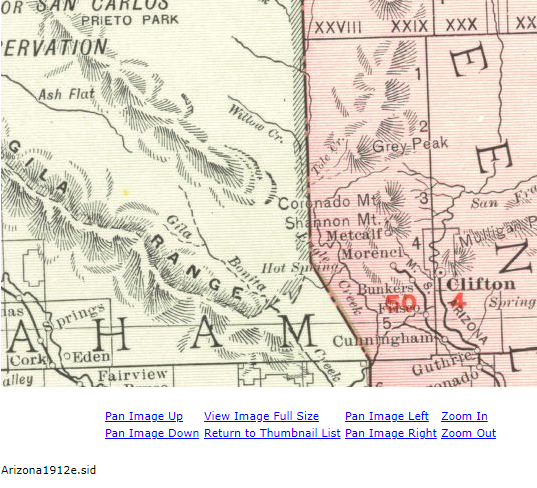

Research done primarily by Richmond’s great grandniece, Dorotha Piechocki (b. 1951), provides a very reasonable estimate of the location of the attack. She located maps drawn in 1880 and 1912 that show Stevens Ranch and, just to the south, “Ash Flat” with an unnamed creek flowing from it near Willow Creek where it flows into Eagle Creek. Springerville resident, E.C. Bunch, as quoted in 1918, said,” [ Creaghe and Richmond ] were killed on Eagle Creek while returning from Clifton and the Gila Valley…” (Farish). Try Google mapping “Eagle Creek Ranch, Arizona” and explore around the area just downstream on Eagle Creek. See what you think. The preponderance of evidence fits. Also, if you Google map “Ash Creek,” the one that comes up is not the one we are interested in.

“Little Stevens” Ranch (Center), Clifton (Lower Right – Red Line), C. Thomas (Camp or Fort Thomas) (Mid-lower Left)

Stevens Ranch would be just above Willow Creek – Eagle Creek confluence.

An article with a May 10 byline ran in the Weekly Arizona Miner stating that it was “reported that Paddy Craigh [sic] had $2,600 with him when he was killed. Nothing has been heard in regard to him or Richmond and it is feared that their bodies were mutilated and thrown into some ravine.” This information used by the newspaper was on the telegraph wires within two days of their bodies being found. How were their names known in Tucson that soon? Family legend had it at $5,000 that Gerald was carrying. One wonders what happened to that money.

All these unknown details are actually irrelevant in that two young men – Gerald was twenty-four, James thirty-two – were violently murdered. It was not a glorious or romantic tale of the “Old West”. I am sure neither Gerald nor James was “… ready”.

They were mourned both by family and contemporaries. While speaking many years later about people he had known in the early days of the Arizona Territory, E.C. Bunch said,”[O]f those whose loss I keenly felt, owning to close association, were Paddy Creaghe and James Richmond…”

A creek crosses the Coronado Trail about twenty miles south of Springerville. St. George named it “Paddy Creek” after his brother, Gerald. The name is still in use today (Google Maps).

Both men, Gerald and James, are memorialized on the Arizona Peace Officer’s Memorial which was dedicated in 1988 on the grounds of the Arizona State Capitol. They are the sixth and seventh names listed (see “Historic Sites”). Due to confusion, perhaps related to the appearance of his signature, Gerald is listed as David Creaghe. The board charged with managing the memorial has been twice informed, and perhaps that can be corrected in the future.

The Officer Down Memorial Page https://www.odmp.org/ has entries for both men, recently updated by Dorotha Piechocki.

Stephen B. Creaghe, July 8, 2015; September 20, 2020

Dorotha S. Piechocki, September 20, 2020

References:

Ball, Larry D.: Desert Lawmen, University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

Barnes, Will C., Arizona Place Names, 1880. Stevens Ranch…Eagle Creek, not far from mouth of Willow Creek.

Barnett, Michael; Letters of Harry Alington Creaghe, 1885 – 1868, 2012. Letters from HAC to home. Includes ship over and early time in Australia. CFHS Library.

Becker, Jack A., Gerald F. Creaghe and James A. Richmond, https://whmths.org/round-valley-history/

Becker, Jack A.: Letter regarding Gerald’s signature. CFHS Collection.

Creaghe, Percy F.S.: Scrapbook entry.

Crosby, George: St. George and Paddy Creaghe, St. John’s Observer, August 8, 1880.

Farish, Thomas Edwin, History of Arizona, Vol. VI, 1918.

Gott, Kendall D.: In Search of an Elusive Enemy: The Victorio Campaign, Combat Studies Institute Press. Victorio’s War – a study of the conflict as insurgency. CFHS Library.

Grand Rapids Daily Times, Tuesday, May 11, 1880: ” P. Craig and James Redmond…Killed at Steven’s Ranche.” Piechocki Collection.

Hutton, Paul Andrew: The Apache Wars, Crown, 2016.

Lowell Journal, Lowell, Michigan, Wednesday, June 2, 1880. Letter from George Hiller to Richmond family regarding attack. Piechocki collection.

Piechocki, Dorotha: James Almeron Richmond, Daughters of the Union Veterans of the Civil War, 18×61-1865: Eva Gray Tent no. 2 – Grand Rapids , Michigan, 2020. https://evagray2.jimdofree.com/our-ancestors/james-richmond/

Official Map of the Territory of Arizona….etc” by E.A. Eckhoff and P. Riecker, Civil Engineers, 1880. https://www.davidrumsey.com/maps5457.html

Utley, Robert: Victorio’s War, The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Aug 2008.

The Weekly Arizona Miner, 1880-05-14, page 1, column 6, under heading “News by Telegraph”, about 1/2 way down the page “Tucson, May 8th – Victorio has a fight in Arizona.” https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/sn82014897/id/803/rec/154

The Weekly Arizona miner, 1880-05-21, page 2, column 4, under heading “Camp Lowell.”

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/sn82014897/id/809/rec/155

White Mountain Historical Society, Springerville AZ. Click on History, scroll down to Learn more about the Round Valley. This site, Round Valley,Az.com was put together by James Becker, great grandson of Gustav Becker, a Springerville pioneer and contemporary of the Creaghes. A very good source. https://whmths.org/round-valley-history/

Wikipedia: Victorio, Battle of Fort Tularosa, Alma Massacre, Victorio’s War.

No Comments